Off to Bagru to one of Jai Texart’s units for my first block-printing workshop. The journey there by car is an experience in itself, travelling on a variety of types of roads, surrounded by permanently honking horns and crazy traffic weaving in and out randomly. We eventually drive through part of the town and into the large unit where we are shown around the premises before anything else happens.

Before any printing, we are shown how natural dyes are made, both animal and vegetable, and the fabrics they are used on – animal and plant-based. We will be using a plant-based fibre (cotton) with plant-based dyes. The room we are sitting in is enough to bring out the alchemist in anyone interested in natural dyes, as I am. Shelves full of many rows of glass jars, all containing mysterious looking ingredients – I could almost imagine Bunsen burners and bubbling jars full of brightly coloured liquids on the table.

Hemant explained that there were three centres in Rajasthan where they use natural dyes, they being one of them , the others in Kutchi, Guijrat, and Kalahasti. He explained how each colour is produced and from which plants. Before 1890, all natural dyes were used in producing coloured fabrics, then synthetic dyes were introduced. With synthetic dyes you can mix colours e.g yellow and blue to give another colour, with natural dyes you cannot. Each one has its’ own properties The extractions are from nature, and some plants have almost disappeared, partly climate change, sometimes for political reasons, and they become increasingly expensive. So as the options are reducing, new dyes need to be discovered.

He explained how indigo blue is made, from leaves on the bushes, also yellows, reds, brown and black – the colours we would be using. First, our cotton was to be treated with a mordant, which if not used, meant the fibres would not catch the dye. We were to use Harda powder, a yellow powder made from the Harda fruit. Red from Alizarin (plus alum), from the tree Malarya – the root is most productive, but the leaves and branches can be used too. Yellow, from Pomegranate rind, Turmeric, Adusa, Red Kashish, Harda flowers, Harsinger, and Arjun-Chal. Black, believe it or not, from horseshoes. When these are constantly hit when being changed, it purifies the metal, and black is obtained from the iron. So – if anyone has any spare horseshoes, send them to Jai Texart, as they are in short supply!

Henna, if boiled in copper gives a good reddish – black. Finally, the fabric colours need to be fast, so Alum is used to this end after printing and the preparation processes. We learned about tree-gum, jaggery (sugar juice cake), guar-gum, lac and other wonderful sounding ingredients. Not only that, most of the plants also have healing medicinal properties, so the dyes on the skin can actually be quite good for it in some cases.

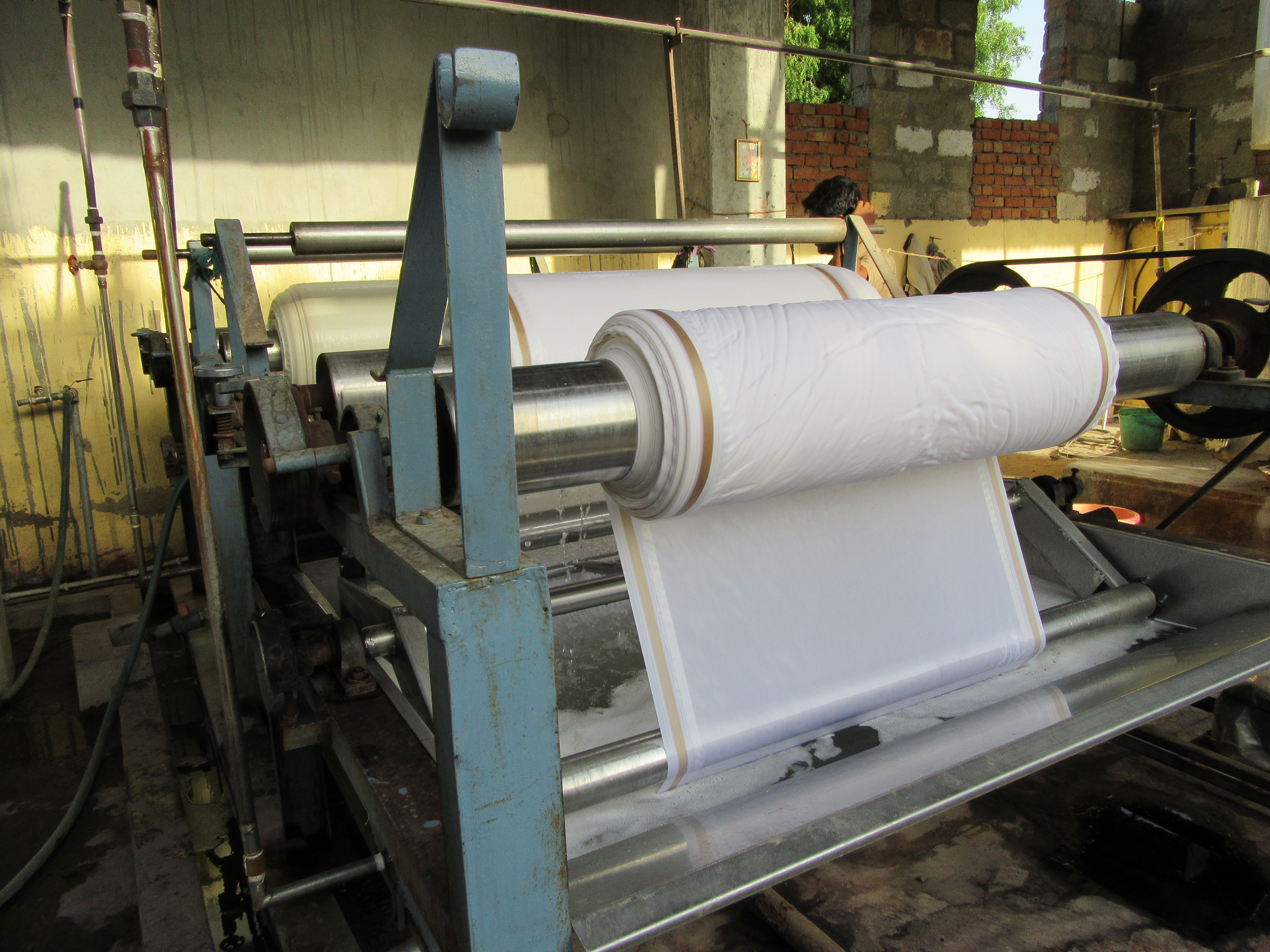

So off to steep our cotton in mordant and get it dried before printing. The treated fabrics are laid out in the hot sun to dry.

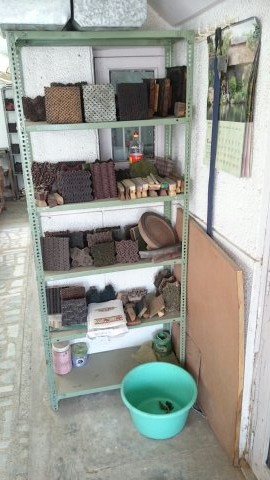

Next, we went into the shed where thousands of carved wood blocks are stored to choose which ones we wanted to use.

Into the printing unit, where our dried fabrics are pinned out tautly on the tables to ensure they don’t move while we print.

Into the printing unit, where our dried fabrics are pinned out tautly on the tables to ensure they don’t move while we print.

Lines and corners are marked with a rule and tailors’ chalk

Then we start our printing, and are shown how to go round corners.

A lot of mistakes, but finished, and can now be treated again and washed. First, our fabrics must be dried again in the sun.

The end of a long, very hot, informative fun day – worth every minute, and I am left even more with a sense of how very much there is to learn and practice.

All content © 2007-2018 Elizabeth Woods. All rights reserved. You may not take or copy any images or content from this site without written permission.

Rakesh Rakesh and Damiyanti holding fabric up for me

Rakesh Rakesh and Damiyanti holding fabric up for me

Racks of beautifully carved wooden blocks used for printing

Racks of beautifully carved wooden blocks used for printing